By Robin Garr

LouisvilleHotBytes.com

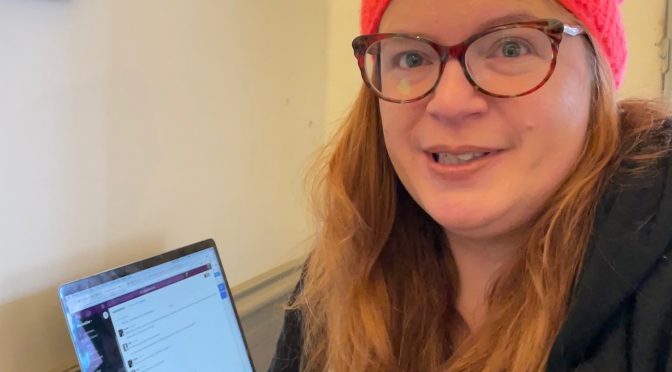

If I was asked to name a local chef most likely to join the Great Resignation, I would never have thought of Meghan Levins. Yet now she’s a full-time webinar monitor for a national virtual education firm.

Look at Levins’ biography, you might think, “There’s a chef for life.” She’s been working in restaurants since she was 15, when her Mom told her that if she wanted a car she was going to have to earn it. She took the challenge, grabbed an after-school job at the Molly Stark Tavern in her home town in New Hampshire.

Her job was bussing tables, she said, but she quickly fell in love with working in the kitchen. Management nurtured her, created a pantry chef job for her, and by her senior year in high school, gave her the recommendation that got her into CIA, the Culinary Institute of America.

Is CIA really is as tough as Chef Michael Ruhlman wrote in his memorable book, “The Making of a Chef”? Absolutely, she says. “It was very military,” she said. “I wouldn’t take it back for anything.” CIA trained her as a chef and started her on a round of kitchen jobs, moving around the country with her former husband, who was in the military: New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, Louisiana, and finally Kentucky.

Meghan lands in Louisville

Nine years ago, when her husband got out of the military, they tried to figure where to go. “New England was too cold, the Northeast was too expensive. “A bunch of people told us we’d like Louisville,” she recalled. “They told me I’d love Louisville, a farm-to-table scene starting up. I was like, ‘You’re joking!’ I thought of this as a rust belt area.”

But they came for a three-day weekend at the peak of autumn’s beauty and, she said, “I just felt connected right away, and here I am.”

She bounced around local kitchens for a while. She became general manager at Taco Punk. She worked at catering jobs, then joined the kitchen staff at 211 Clover Lane.

Then, when Monnik Beer Co. invited her in as executive chef at its October 2015 opening, Levins felt that she’d found her way home. “They let me be me,” she said.

But all things change, and after five years or so, she received a great-looking offer and left Monnik. That didn’t last, but then Chef Allen Heintzmann, who’d been her boss at 211 Clover Lane, asked her to help out for a few weeks at Louisville Boat Club. “It was good money,” she said, “and I could figure my shit out.”

Then came Covid

And then Covid happened.

“?I could see the staff shortages coming a mile away,” she said. “It was bad, and exhausting enough, even before covid. And then I was given a very lucky and rare opportunity to take a peek at a totally different career, and jumped on it just in case.”

She was already working part-time as webinar monitor for BeaconLive, a virtual education company where she had moonlighted before. “Now they wanted me to work full time in that position.”

The Great Resignation was already under way, with cooks and servers fleeing. “Knowing the labor situation in the hospitality industry, I knew anyone in a salaried position in that industry would carry the bulk of the load,” she said. “I was given a very lucky and rare opportunity to take a peek at a totally different career and jumped on it,” she said.

“I already had in mind that around 40 was when I’d start looking to get out of restaurants, but I did think it would still be in the industry in some capacity. Oh, well!”

Looking to the future

With restaurant workers leaving in droves, how does Levins see things going for the industry?

“If all of this came as a surprise to people, they never worked in a restaurant before,” she said. “All the problems of covid were already going on before. Owners and chefs have been fighting over labor and supplies constantly. But Covid changed everything. When chefs got laid off and got new jobs, they realized they could control their hours. They realized how much better it was.

“Covid broke the fourth wall. Before, you keep all that shit secret. The show must go on. If you were working with only one chef and server, you kept it secret and pushed on. Now it’s out in the open. Line cooks haven’t had raises for 20 years.

“I was paying cooks $12 an hour 20 years ago, and that’s still average wage in this market.”

So where is this runaway train going? “It just seems like the industry is always going to adapt and overcome,” Levins said. “A lot of restaurants will go out of business. People are gong to have to start expecting to pay more for food in general. From the farmers to the processors, it’s all changed by covid from the top down. There have always been problems that covid just glaringly exposed.

“So where all this points, if restaurants are going to survive, they need to become a lot more expensive, but I don’t know if they can. I’ve been saying this forever, people are going to have to acclimate themselves to higher prices for food. We’ve got to get people off the idea of cheap food or it will be impossible to meet the costs of supplies and labor.”

So, approaching the end of the second year of the pandemic, what would it take to bring Chef Meghan Levins back to the business?

“I’ll be back when I can make my own dreams come true in the industry,” she said. “Nothing would have kept me from at least taking a shot at something different, but I knew the industry would always be there if it didn’t work out.”